I have been working as a ‘T shaped’, multi-disciplined Business Analyst on government software development projects for about five years now. I wanted to take an opportunity to reflect on what a typical day might look like ‘on the ground’, right there in the detail. Unfortunately, I’ve been unable to come up the perfect description, or in fact any description of what a typical day might look like. One day is very rarely the same as another. However, it has been possible to take a look across the board, between the different government organisations and pull out some common themes. Here I will discuss ‘Software development methodology’ and this blog will be part of a series that covers:

- Software development methodology

- Conflict

- Scope and deliverability

- Stakeholders and the team

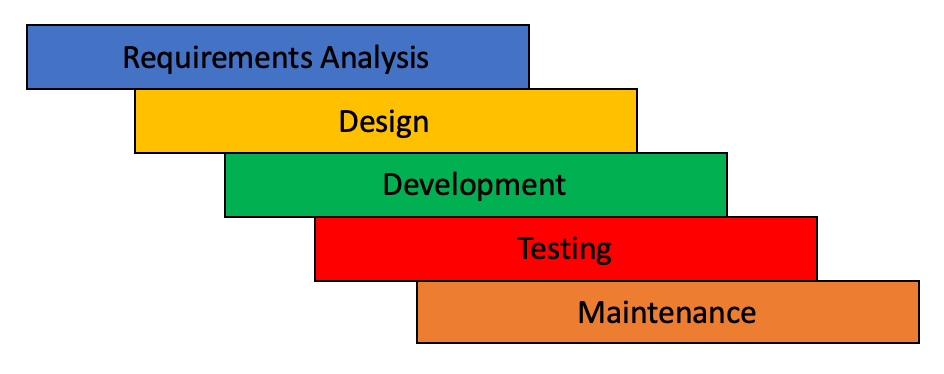

Let’s start by briefly taking a look at the structure of a traditional ‘Waterfall’ project. Here, progress is made in distinct phases, with little or no overlap between each other. At the requirements phase, the Business Analysts understands what the problem is. They then gather the requirements that the system will be designed, developed and tested against.

At the design phase, the system including forms, structure, database etc is designed in a way that ensures the requirements can be handled. This type of design involves the likes of a solutions architect, more-so than an Interaction, Content or Service designer that we might be familiar with on government projects.

Once the design is completed, development takes place. Development should include all requirements that have been deemed as in scope for the project. Once complete, testing will commence. When the system has gone through all of these phases, it will enter into maintenance. Once the system is considered stable, the project comes to an end.

There are many strengths to a waterfall project, many big systems have been developed for generations using this very approach. Whilst it is important to recognise this, at the same time there are some weaknesses too. These include:

- Benefits can only ever be realised at the end of a project

- The work for each phase often takes place in silos, leading to misunderstanding and misrepresentation of the requirements

- The problems can move on since the requirements were gathered, therefore the solution is no longer fit for purpose

- The project runs over budget

- The project runs over time

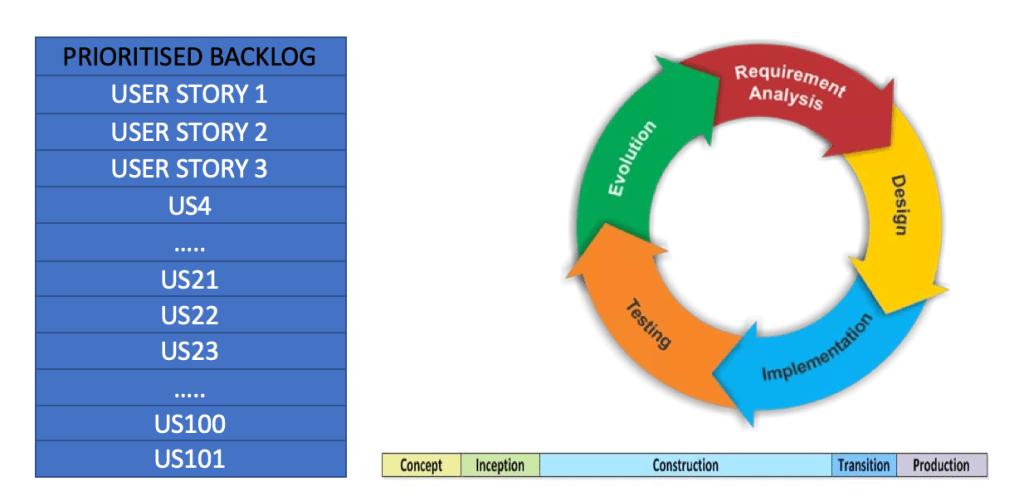

Now for an agile approach. There are many flavours to this, but let’s take a look at Scrum. We start with a concept. Once this is proven to be a worthwhile investment, an inception can begin. The inception is the beginning of an agile project where the team get together to discuss the vision, goals, constraints and potential issues amongst a number of other topics. When the inception is completed, the construction phase can begin.

In Scrum we work in ‘sprints’, the length of which would have been defined at the inception too. A key difference between Waterfall and Agile is that where phases are staggered in the former, they happen simultaneously in the latter. There are ‘Themes’ and ‘Epics’, that can be broken down into user stories, creating a ‘product backlog’. These are prioritised for development by the Product Owner, who is responsible for the overall quality of the product.

Meanwhile development and testing for the priority features will also be taking place. Code is ‘shipped’ frequently, often every sprint. This allows the benefits to be realised much earlier. If problems have been uncovered and lessons learned since a previous deployment, an iteration can take place. This ensures that the product remains fit for purpose throughout the life cycle of the project.

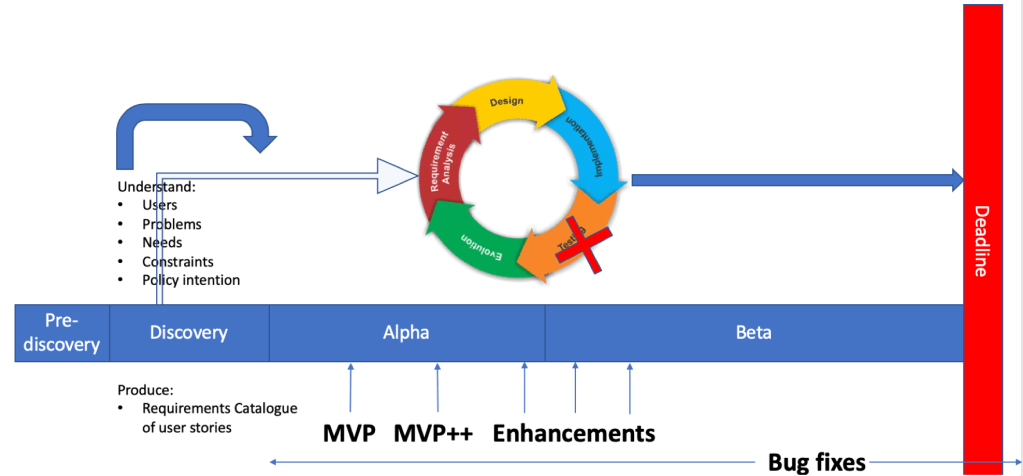

Now that we’ve had a brief overview of both Waterfall and Agile, let’s discuss Government Digital Service (GDS) and the software development approach that government projects use. We’re going to take a look at what should happen in theory, compared to what often happens in practice. It’s important to note that GDS Service Standard No 7. is to ‘create the service using agile, iterative user-centred methods.’

Above is a depiction of what should happen. The pre-discovery is the feasibility phase, this is where the project should formally be commissioned. Then there is a discovery, centred around the user and the problems that the user experiences in their current processes or journey. As well as understanding this, we want to understand user needs and any constraints that may be faced. As we are working in government and policy plays a big part, we should understand the intention behind the policy too. It would be great to come out of discovery with some sort of scope, a backlog of user needs and a product roadmap to take us from where we are, to where we want to go. We want to assess and reassess all of the above from discovery throughout the life cycle of the project.

Then we have Alpha, this is where we can first try to solve the problems that the user is facing. We take the lessons we learned since discovery and put together a journey that meets the user needs. Here we should focus on a Minimum Viable Product (MVP). At this point, we should continuously research and prototype, iterating and providing multiple possible options to the user. This should be ongoing until the point we are comfortable with a basic journey that can be built and continue to be iterated on in Beta. Now we go to an assessment with a GDS Panel, where the team should be able to demonstrate that they understand the users, wider context and problems. We should also be able to demonstrate that the journey we are proposing helps to solve these problems and fulfil user needs. Assuming we are successful in this, we can go into Beta and start to build software using agile, iterative methods.

During Beta, all of the good stuff we’ve talked about so far should continue to take place. However, now we can start to build concurrently in a ‘development environment’. We’re going to assume that we are using Scrum here, for the simple reason that all of the projects I’ve worked on in government have opted for this as their preferred approach. Now we can start to work towards the Scrum process we described above, breaking down Epics and Themes, creating and prioritising user stories with the Product Owner and working in sprints until we have covered the scope of an MVP.

At this point we go to another assessment, prove that we have worked towards the service standard and assuming we pass, move into Private Beta. In Private Beta we have a small user group that is using our newly developed functionality. We continue to learn and iterate on the lessons until we get to a position where we are comfortable moving into Public Beta, on-boarding more users, learning more lessons, researching, prototyping and iterating further before ‘going live’.

What often happens actually looks more like this. The understanding of users, problems, their needs, constraints and policy intention is condensed into the discovery and doesn’t get revisited throughout the life cycle of the project. The requirements analysis moves to the left into the discovery and user stories start to be written early, often leading to a full waterfall type ‘requirements catalogue’ being produced and very rarely iterated on.

During Alpha, when we should be prototyping and testing, we start to develop too, rushing the important activities that Alpha should be reserved for. An MVP is delivered ‘undercover’, shhhh, not to be mentioned at the assessment. This takes on various forms before resembling anything close to an MVP. Testing gets squashed because of the pace that development is taking place at. There are often far too many developers in proportion to Quality Assurance Testers. Demand on the Quality Assurance Testers means that bugs slip through in high volume. We also start to add enhancements early on. All of this results in bug fixes from start to finish.

This model results in conflict within the team. The next blog will aim to describe what the conflict looks like and how it is triggered by the events described above. A lot of this could be mitigated with a more realistic scope and a less fixed deadline, the topic of a future blog.